Remembering the King

The everyday-ness and humanity of Arnold Palmer touched this one local sportswriter

by Bob Robinson

(In the upcoming November issue of Pacific Northwest Golfer magazine, look for more responses from the Northwest golf community to Arnold Palmer’s death, and how Palmer touched our region.)

Several entrants in the 1998 Fred Meyer Challenge were on the driving range, warming up for their opening rounds at the Reserve Vineyards and Golf Club in the Portland suburbs. Among them was Arnold Palmer who would be teeing off in about 45 minutes as host pro Peter Jacobsen’s partner.

As The Oregonian’s golf writer, I needed to talk to him and I didn’t want to wait until after the day’s play when he would be available in the media room in front of about 40 writers and broadcasters.

My sports editor had called and asked me to do a sidebar story on Palmer’s health, which had been rumored to be a problem despite his seemingly successful prostate cancer surgery in January of 1997.

I wasn’t supposed to go inside the ropes surrounding the range but I took a chance, slid under the ropes while a marshal wasn’t looking and walked up to Palmer.

“Arnie, I’m sorry to bother you but I’d really appreciate it if I could ask you a couple of questions,” I said. I knew that a majority of tour pros would have turned me down. Not Palmer. “Sure enough,” he said before guiding me to an open area away from his fellow players. The marshal, his anger showing, came running but Arnie waved him away. “It’s okay, no problem,” he said.

Then Palmer willingly explained to me that he had had a recent PSA (Prostate Specific Antigen). “It showed a slight increase,” he said. “It wasn’t much, but it was enough that the doctor recommended that I have (radiation) treatments. He told me I might be all right without them but the chances are that I could have a problem in the long run.”

Palmer said that his treatments, which would begin a few days after the Challenge, would last for seven weeks, five days a week. “I’ll be at home (in Latrobe, Pa.) the whole time,” he said. “On the days of my treatments, I’ll be up at 5 a.m., in the doctor’s office by 7:45 and be out of there at about 8:30.”

He seemed upbeat and expressed confidence that everything would work out. “I’ll be back playing golf in no time,” he said.

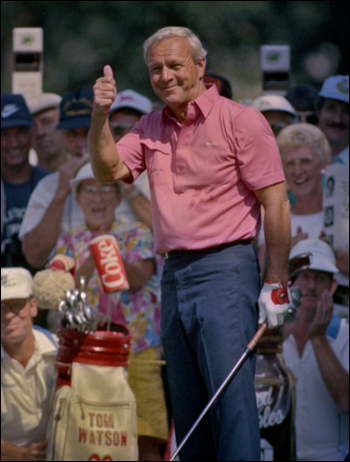

Finally, as I was about to leave, he inquired if I had had a PSA recently. I replied in the affirmative and told him about a re-section of the prostate that I had had in 1991. “Keep getting those PSAs,” he said. “They are so important.” Then he gave me a thumbs-up sign and headed back to his golf clubs.

This experience came to mind on Sept. 25, 2016, when Palmer died in Pittsburgh, Pa. He was 87. The loss was felt worldwide because Palmer was one of a kind – the so-called “King” whose talent, engaging personality and humble attitude were like a magnet to golf fans who became self-appointed members of “Arnie’s Army.”

And who can forget how, with a dogged competitiveness, an unorthodox swing and go-for-broke style of play, he was the most responsible for lifting golf out of the dark ages? With Jack Nicklaus, he turned the sport into a major television attraction in the early 1960s. Later, he became an accomplished pilot with his own airplane, a marketing icon, a golf course designer and a co-founder of Golf Channel.

And while winning seven of golf’s majors, Palmer was amazing in the way he retained his humility. He constantly had exchanges with fans, winked at women in the gallery and willingly signed autographs for as long as it took to satisfy the masses. His signature always was flawless, too. “When a fan asks you for an autograph, he or she is honoring you, so you owe it to them to sign an autograph they can read.”

He made the latter comment to Jacobsen one day when he saw the then PGA Tour rookie scribbling his name for an autograph seeker. “I never forgot it,” said Jacobsen who followed Palmer’s suggestion that he shape up with the pen.

Palmer also exhibited exceptional patience and consideration with the media as he showed that day when I approached him on the driving range. Another time, when I was working on a story detailing how Palmer and Nicklaus felt about each other on and off the course, he made himself available for an early morning phone call and answered my questions for about 15 minutes.

Among his comments in that interview was this one about his relationship with Nicklaus: “We would have at it on the course but there was nothing bitter about it. We always were friends and we became even better friends late in our careers.”

My first experience covering Palmer was at the 1966 U.S. Open at the Olympic Club in the San Francisco suburbs. I was one of the few writers who walked the tournament’s final nine holes when Palmer shockingly blew a seven-shot lead, eventually losing an 18-hole playoff to Billy Casper the next day. I couldn’t believe the class he showed after both the closing 18 and the playoff. He was hurting inside but he bravely answered questions and hid his heartbreak.

He also made a phone call the night before the playoff to his caddie, Mike Reasor of Seattle. “He apologized to me for not winning,” Reasor said. “I was on my knees with tears in my eyes. I couldn’t believe, knowing how he felt, that he would take the time to call me.”

No wonder that, after the playoff, Casper admitted to being lost for words as he approached Palmer. Finally, he was moved to say, “Arnold, I’m sorry.” And, he said, he truly meant it.

Bob Robinson started covering golf for The Oregonian in the mid-1960s. He has covered 24 major championships, two Ryder Cups, and more than 30 LPGA Tour events.