Northwest Influential: The Architects

by Tony Dear

Golf in the Pacific Northwest has a rich history, full of characters, frontrunners, visionaries, boom-and-bust epics, and too-good-to-be-true (but mostly they really are true) tales.

This is the fourth in a series of articles, highlighting the people who have made this far corner of the continent our center of the golf universe, and have shaped the way we play the game.

Lists are dangerous things. They are inevitably incomplete, subjective, and all-too-short. So here we go……

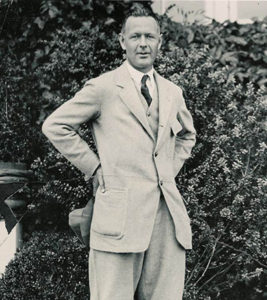

Chandler Egan

Born in Chicago in 1884, H. Chandler Egan attended Harvard University where he captained the golf team and won an NCAA individual title in 1902. Two years later, he won silver at the Olympic Games in St. Louis, and the U.S. Amateur, a title he successfully defended the following year.

In 1911, Egan upped sticks and headed west to Oregon where he purchased a 115-acre apple and pear orchard near Medford for $75,000. Fruit-farming wasn’t enough to sustain the former (and future – five-time PNGA Men’s Amateur winner and 1926 California State Amateur winner) golf champion’s imagination, so he moonlighted as a golf course architect and eventually became perhaps the leading designer in the Pacific Northwest in the 1920s, during which he designed, or made revisions to, Rogue Valley, Tualatin, Waverley, Eastmoreland, Oswego Lake, Riverside, and several others.

He teamed with Alister MacKenzie in preparing Pebble Beach for the 1929 U.S. Amateur, making a number of significant changes. He also worked with MacKenzie and Robert Hunter at Sharp Park in Pacifica, Calif. in 1932. In Washington, he designed Spokane’s excellent Indian Canyon, West Seattle, and Everett’s Legion Memorial. It was while working on Legion Memorial in 1936 that Egan contracted pneumonia and died. He was inducted into the PNGA Hall of Fame in 1985.

Arthur Vernon Macan

An Irishman by birth, lawyer by profession, and competitive golfer from his early teens, A.V. Macan emigrated to Canada in 1912, at the age of 30, establishing a home in Victoria, B.C. He quickly tired of practicing law and moved into golf course design, scoring his first success at Colwood GC (now Royal Colwood) in 1913.

Macan enlisted and fought with the Canadian Expeditionary Force during World War I, and was seriously injured at the Battle of Vimy Ridge in 1917. He lost his left foot and recovered in a London hospital before returning to British Columbia in 1920. Despite his disability, Macan continued to play competitive golf and forged an impressive career as a golf course architect.

Over the next 40 years, Macan completed several fine renovations and built numerous highly-regarded courses – Inglewood, Broadmoor and Fircrest in the Puget Sound area; California GC in San Francisco; Manito in Spokane; Alderwood and Columbia-Edgewater in Portland; and Marine Drive, Langara, and Shaughnessy in Vancouver, B.C.

Macan was inducted into the PNGA Hall of Fame in 1989.

John Fought

John Fought could quite easily have appeared in the “Players” category of this series, but has now spent more than half his life as an architect, so here he is.

Born in Portland in 1954, Fought won the U.S. Amateur in 1977, played on the U.S. Eisenhower and Walker Cup teams, was named Rookie of the Year on the PGA Tour in 1979 and finished his career (injury put an end to his competitive playing days in 1985) with two wins and a dozen top-10 finishes, including a tie for fifth at the 1983 PGA Championship.

Fought remembers talking with Jack Nicklaus about course architecture sometime in the early 1980s. Nicklaus suggested he speak with his senior designer Bob Cupp, for whom Fought would eventually begin work as an associate. His first major project with Cupp was designing the two courses at Pumpkin Ridge. The superb Crosswater in Sunriver followed three years later, shortly after which Fought set up his own company, based in Scottsdale, Ariz.

An admirer of Golden Age designers such as Donald Ross, Alister Mackenzie and A.W. Tillinghast, Fought has compiled an impressive portfolio over the last 20 years. Highlights include the Players Course at the Indian Wells (Calif.) Golf Resort, Sand Hollow in Hurricane, Utah, both courses at The Gallery in Marana, Ariz., two Washington beauties – Trophy Lake and Washington National; and his own personal favorite – Windsong Farm in Minneapolis. Fought has also completed over a dozen renovations, including a highly-acclaimed redesign of Black Butte Ranch’s Glaze Meadow course.

In 2009, Fought was inducted into the PNGA Hall of Fame.

John Harbottle III

John Harbottle III was the eldest son of PNGA Hall of Fame golfers Dr. John Harbottle and Patricia Lesser Harbottle, and graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in landscape architecture before going to work for Pete Dye in 1984. He worked on some of America’s most acclaimed courses under Dye, and spent a lot of time in Scotland and Ireland studying the great links.

Thanks to his travels throughout the British Isles, Harbottle developed a sound understanding of nature’s role in creating golf courses. After setting up his own company, he gained a reputation for treading lightly and making the most of whatever natural features he had to work with – an approach to design he demonstrated skillfully at Gold Mountain’s Olympic Course in Bremerton, Wash., BanBury GC in Eagle, Idaho, Juniper GC in Redmond, Ore.; and especially Palouse Ridge in Pullman, Wash., his last course before suffering a fatal heart attack in May 2012, at the age of 53.

Nick Schaan, now a senior associate with David McLay Kidd, began his design career at Harbottle’s firm in 2003. “Besides being a great boss and having a sound, practical approach to designing golf courses, John was just a decent human being,” he says. “He always got on well with clients and superintendents at the courses he built. You sometimes need an ego to get anywhere in this business, but John had none. He wasn’t interested in being high-profile, just doing the best job possible.”

David McLay Kidd

As a boy, the young David McLay Kidd watched as his father Jimmy, then the head greenkeeper at Gleneagles in Pethshire, Scotland, re-established James Braid’s original model for both the King’s and Queen’s courses. Golf course architecture books filled Jimmy’s shelves and young David read them all.

By high school in Auchterarder, he knew exactly what he wanted to do.

After earning a horticulture qualification at Writtle College in Essex, England, Kidd spent a brief period with English designer Howard Swan before returning to Gleaneagles, which contracted out his design services.

In 1991, Kidd toured a site near Sunriver in Oregon that developers had earmarked for a Gleneagles-style resort. The project never happened, but Kidd fell for the place and daydreamed of one day living in such an incredible place.

Just three years later, he got a call from a greeting card company executive who had acquired an interesting property just outside the village of Bandon on the Oregon coast. It was 240 miles west of Sunriver, 140 miles from Eugene, and five hours south of Portland, but this Chicago guy planned on building a traditional, linksy-style golf course there anyway.

Mike Keiser wanted a Scot to design his course on the cliffs above the Pacific. Hiring Jimmy Kidd and his inexperienced architect son was a huge risk, but Keiser obviously saw something few others did. The Kidds began work clearing the site in 1994, and David eventually moved to Coos Bay in the late ‘90s as the course was nearing completion.

It opened in 1999 and was an instant success. The obscure David McLay Kidd – in his mid-20s when work had begun at Bandon – was suddenly something of an architecture rock star.

He clearly had talent but would need to repeat this early showing if he was to realize his potential and establish himself among the industry’s leading lights, and he’d have to move out of Coos Bay, which would prove unsuitable for a rapidly-expanding golf course architecture firm. He would eventually become a resident of Bend, Ore. in 2006, and is still headquartered there.

Kidd quickly proved that what had happened at Bandon Dunes was no flash in the pan. Over the next 18 years, the hits just kept coming. Nanea in Hawaii, Huntsman Springs in Idaho, the Castle Course and Machrihanish Dunes in Scotland, Tetherow in Oregon, Guacalito in Nicaragua, Gamble Sands in Washington, and Mammoth Dunes in Wisconsin among others helped him join a group of contemporaries regarded as the finest golf course designers in the world today.

Dan Hixson

A native of Eugene, Ore., Hixson got an early lesson in golf course design when his father, the well-known PGA pro at Hidden Valley GC, took him to Eugene Country Club, where his grandparents were members, in 1968.

“I was just a kid and we were only there for half an hour or so,” Hixson remembers. “But it was at the time Robert Trent Jones was redesigning it. Until then I thought golf courses were just there. I didn’t realize somebody actually built them. I remember being quite fascinated.”

Hixson would spend his teens and early adulthood playing professionally and as PGA head professional at Columbia Edgewater throughout most of the 1990s.

In 1998, Hixson decided to leave Columbia Edgewater, downsize everything, and do whatever was necessary to become a course architect – even if that meant digging ditches and making little money to begin with. In the first few years, he’d build a new tee here or reshape a green there. He then got a chance to build the Par 3 course at Columbia Edgewater alongside Bunny Mason.

That job was a success, so other private clubs – Portland GC, Riverside GCC, Rainier CC – came calling. And then, in 2005, he landed his first major original design job when Carla and Rex Smith hired him to build 18 holes on a largely-wooded site 20 minutes south of the Bandon Dunes Golf Resort. Bandon Crossings, opened in 2007, was a hit, as was Hixson’s next course – the excellent Wine Valley outside Walla Walla.

Hixson’s burgeoning design career stalled when the Great Recession hit, but he did get another chance to build something new not long after Wine Valley opened. He began work on two reversible courses – 36 holes and 27 greens – at Silvies Valley Ranch, in eastern Oregon, towards the end of 2009. For one reason or another, however, they didn’t open until the summer of 2017 when golfers at last saw how complex and fascinating a routing Hixson had created.

A big fan of Alister MacKenzie’s designs, Hixson is currently working on a new course tentatively called Callahan Ridge, outside Roseburg, Ore.